Binomial coefficient

In mathematics, the binomial coefficient  is the coefficient of the x k term in the polynomial expansion of the binomial power (1 + x) n.

is the coefficient of the x k term in the polynomial expansion of the binomial power (1 + x) n.

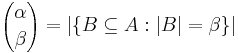

In combinatorics,  is interpreted as the number of k-element subsets (the k-combinations) of an n-element set, that is the number of ways that k things can be "chosen" from a set of n things. Hence,

is interpreted as the number of k-element subsets (the k-combinations) of an n-element set, that is the number of ways that k things can be "chosen" from a set of n things. Hence,  is often read as "n choose k" and is called the choose function of n and k.

is often read as "n choose k" and is called the choose function of n and k.

The notation  was introduced by Andreas von Ettingshausen in 1826,[1] although the numbers were already known centuries before that (see Pascal's triangle). Alternative notations include C(n, k), nCk, nCk,

was introduced by Andreas von Ettingshausen in 1826,[1] although the numbers were already known centuries before that (see Pascal's triangle). Alternative notations include C(n, k), nCk, nCk,

,[2] in all of which the C stands for combinations or choices.

,[2] in all of which the C stands for combinations or choices.

Definition

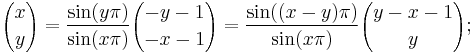

For natural numbers (taken to include 0) n and k, the binomial coefficient  can be defined as the coefficient of the monomial Xk in the expansion of (1 + X)n. The same coefficient also occurs (if k ≤ n) in the binomial formula

can be defined as the coefficient of the monomial Xk in the expansion of (1 + X)n. The same coefficient also occurs (if k ≤ n) in the binomial formula

(valid for any elements x,y of a commutative ring), which explains the name "binomial coefficient".

Another occurrence of this number is in combinatorics, where it gives the number of ways, disregarding order, that a k objects can be chosen from among n objects; more formally, the number of k-element subsets (or k-combinations) of an n-element set. This number can be seen to be equal to the one of the first definition, independently of any of the formulas below to compute it: if in each of the n factors of the power (1 + X)n one temporarily labels the term X with an index i (running from 1 to n), then each subset of k indices gives after expansion a contribution Xk, and the coefficient of that monomial in the result will be the number of such subsets. This shows in particular that  is a natural number for any natural numbers n and k. There are many other combinatorial interpretations of binomial coefficients (counting problems for which the answer is given by a binomial coefficient expression), for instance the number of words formed of n bits (digits 0 or 1) whose sum is k, but most of these are easily seen to be equivalent to counting k-combinations.

is a natural number for any natural numbers n and k. There are many other combinatorial interpretations of binomial coefficients (counting problems for which the answer is given by a binomial coefficient expression), for instance the number of words formed of n bits (digits 0 or 1) whose sum is k, but most of these are easily seen to be equivalent to counting k-combinations.

Several methods exist to compute the value of  without actually expanding a binomial power or counting k-combinations.

without actually expanding a binomial power or counting k-combinations.

Recursive formula

One has a recursive formula for binomial coefficients

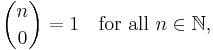

with as initial values

The formula follows either from tracing the contributions to Xk in (1 + X)n−1(1 + X), or by counting k-combinations of {1, 2, ..., n} that contain n and that do not contain n separately. It follows easily that  when k > n, and

when k > n, and  for all n, so the recursion can stop when reaching such cases. This recursive formula then allows the construction of Pascal's triangle.

for all n, so the recursion can stop when reaching such cases. This recursive formula then allows the construction of Pascal's triangle.

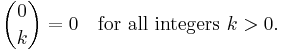

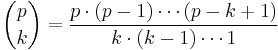

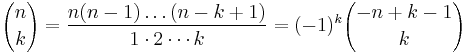

Multiplicative formula

A more efficient method to compute individual binomial coefficients is given by the formula

This formula is easiest to understand for the combinatorial interpretation of binomial coefficients. The numerator gives the number of ways to select a sequence of k distinct objects, retaining the order of selection, from a set of n objects. The denominator counts the number of distinct sequences that define the same k-combination when order is disregarded.

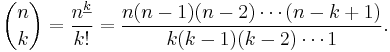

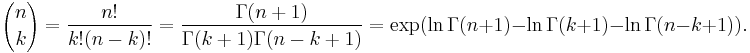

Factorial formula

Finally there is a formula using factorials that is easy to remember:

where n! denotes the factorial of n. This formula follows from the multiplicative formula above by multiplying numerator and denominator by (n − k)!; as a consequence it involves many factors common to numerator and denominator. It is less practical for explicit computation unless common factors are first canceled (in particular since factorial values grow very rapidly). The formula does exhibit a symmetry that is less evident from the multiplicative formula (though it is from the definitions)

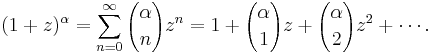

Generalization and connection to the binomial series

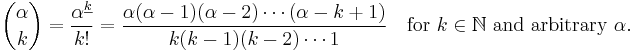

The multiplicative formula allows the definition of binomial coefficients to be extended[note 1] by replacing n by an arbitrary number α (negative, real, complex) or even an element of any commutative ring in which all positive integers are invertible:

With this definition one has a generalization of the binomial formula (with one of the variables set to 1), which justifies still calling the  binomial coefficients:

binomial coefficients:

This formula is valid for all complex numbers α and X with |X| < 1. It can also be interpreted as an identity of formal power series in X, where it actually can serve as definition of arbitrary powers of series with constant coefficient equal to 1; the point is that with this definition all identities hold that one expects for exponentiation, notably

If α is a nonnegative integer n, then all terms with k > n are zero, and the infinite series becomes a finite sum, thereby recovering the binomial formula. However for other values of α, including negative integers and rational numbers, the series is really infinite.

Pascal's triangle

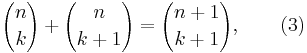

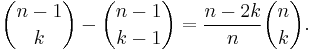

Pascal's rule is the important recurrence relation

which can be used to prove by mathematical induction that  is a natural number for all n and k, (equivalent to the statement that k! divides the product of k consecutive integers), a fact that is not immediately obvious from formula (1).

is a natural number for all n and k, (equivalent to the statement that k! divides the product of k consecutive integers), a fact that is not immediately obvious from formula (1).

Pascal's rule also gives rise to Pascal's triangle:

-

0: 1 1: 1 1 2: 1 2 1 3: 1 3 3 1 4: 1 4 6 4 1 5: 1 5 10 10 5 1 6: 1 6 15 20 15 6 1 7: 1 7 21 35 35 21 7 1 8: 1 8 28 56 70 56 28 8 1

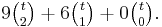

Row number n contains the numbers  for k = 0,…,n. It is constructed by starting with ones at the outside and then always adding two adjacent numbers and writing the sum directly underneath. This method allows the quick calculation of binomial coefficients without the need for fractions or multiplications. For instance, by looking at row number 5 of the triangle, one can quickly read off that

for k = 0,…,n. It is constructed by starting with ones at the outside and then always adding two adjacent numbers and writing the sum directly underneath. This method allows the quick calculation of binomial coefficients without the need for fractions or multiplications. For instance, by looking at row number 5 of the triangle, one can quickly read off that

- (x + y)5 = 1 x5 + 5 x4y + 10 x3y2 + 10 x2y3 + 5 x y4 + 1 y5.

The differences between elements on other diagonals are the elements in the previous diagonal, as a consequence of the recurrence relation (3) above.

Combinatorics and statistics

Binomial coefficients are of importance in combinatorics, because they provide ready formulas for certain frequent counting problems:

- There are

ways to choose k elements from a set of n elements. See Combination.

ways to choose k elements from a set of n elements. See Combination. - There are

ways to choose k elements from a set of n if repetitions are allowed. See Multiset.

ways to choose k elements from a set of n if repetitions are allowed. See Multiset. - There are

strings containing k ones and n zeros.

strings containing k ones and n zeros. - There are

strings consisting of k ones and n zeros such that no two ones are adjacent.

strings consisting of k ones and n zeros such that no two ones are adjacent. - The Catalan numbers are

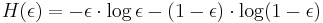

- The binomial distribution in statistics is

- The formula for a Bézier curve.

Binomial coefficients as polynomials

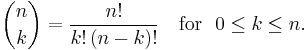

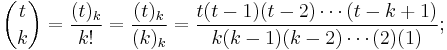

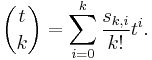

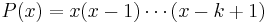

For any nonnegative integer k, the expression  can be simplified and defined as a polynomial divided by k!:

can be simplified and defined as a polynomial divided by k!:

This presents a polynomial in t with rational coefficients.

As such, it can be evaluated at any real or complex number t to define binomial coefficients with such first arguments. These "generalized binomial coefficients" appear in Newton's generalized binomial theorem.

For each k, the polynomial  can be characterized as the unique degree k polynomial p(t) satisfying p(0) = p(1) = ... = p(k − 1) = 0 and p(k) = 1.

can be characterized as the unique degree k polynomial p(t) satisfying p(0) = p(1) = ... = p(k − 1) = 0 and p(k) = 1.

Its coefficients are expressible in terms of Stirling numbers of the first kind, by definition of the latter:

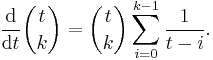

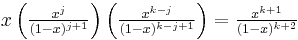

The derivative of  can be calculated by logarithmic differentiation:

can be calculated by logarithmic differentiation:

Binomial coefficients as a basis for the space of polynomials

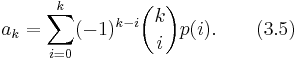

Over any field containing Q, each polynomial p(t) of degree at most d is uniquely expressible as a linear combination  . The coefficient ak is the kth difference of the sequence p(0), p(1), …, p(k). Explicitly,[note 2]

. The coefficient ak is the kth difference of the sequence p(0), p(1), …, p(k). Explicitly,[note 2]

Integer-valued polynomials

Each polynomial  is integer-valued: it takes integer values at integer inputs. (One way to prove this is by induction on k, using Pascal's identity.) Therefore any integer linear combination of binomial coefficient polynomials is integer-valued too. Conversely, (3.5) shows that any integer-valued polynomial is an integer linear combination of these binomial coefficient polynomials. More generally, for any subring R of a characteristic 0 field K, a polynomial in K[t] takes values in R at all integers if and only if it is an R-linear combination of binomial coefficient polynomials.

is integer-valued: it takes integer values at integer inputs. (One way to prove this is by induction on k, using Pascal's identity.) Therefore any integer linear combination of binomial coefficient polynomials is integer-valued too. Conversely, (3.5) shows that any integer-valued polynomial is an integer linear combination of these binomial coefficient polynomials. More generally, for any subring R of a characteristic 0 field K, a polynomial in K[t] takes values in R at all integers if and only if it is an R-linear combination of binomial coefficient polynomials.

Example

The integer-valued polynomial 3t(3t + 1)/2 can be rewritten as

Identities involving binomial coefficients

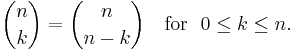

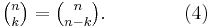

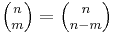

For any nonnegative integers n and k,

This follows from (2) by using (1 + x)n = xn·(1 + x−1)n. It is reflected in the symmetry of Pascal's triangle. A combinatorial interpretation of this formula is as follows: when forming a subset of  elements (from a set of size

elements (from a set of size  ), it is equivalent to consider the number of ways you can pick

), it is equivalent to consider the number of ways you can pick  elements and the number of ways you can exclude

elements and the number of ways you can exclude  elements.

elements.

The factorial definition lets one relate nearby binomial coefficients. For instance, if k is a positive integer and n is arbitrary, then

and, with a little more work,

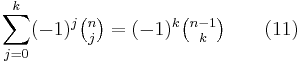

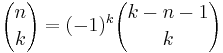

Powers of -1

A special binomial coefficient is  ; it equals powers of -1:

; it equals powers of -1:

Series involving binomial coefficients

The formula

is obtained from (2) using x = 1. This is equivalent to saying that the elements in one row of Pascal's triangle always add up to two raised to an integer power. A combinatorial interpretation of this fact involving double counting is given by counting subsets of size 0, size 1, size 2, and so on up to size n of a set S of n elements. Since we count the number of subsets of size i for 0 ≤ i ≤ n, this sum must be equal to the number of subsets of S, which is known to be 2n. That is, Equation 5 is a statement that the power set for a finite set with n elements has size 2n.

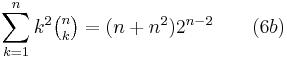

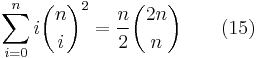

The formulas

and

follow from (2), after differentiating with respect to x (twice in the latter) and then substituting x = 1.

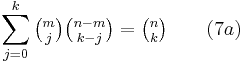

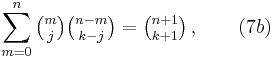

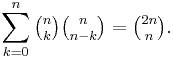

The Chu-Vandermonde identity, which holds for any complex-values m and n and any non-negative integer k, is

and is found by expanding (1 + x)m (1 + x)n − m = (1 + x)n with (2). When m = 1, equation (7a) reduces to equation (3).

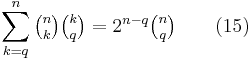

A similar looking formula, which applies for any integers j, k, and n satisfying 0 ≤ j ≤ k ≤ n, is

and is found by expanding  with

with

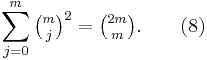

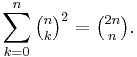

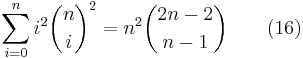

From expansion (7a) using n=2m, k = m, and (4), one finds

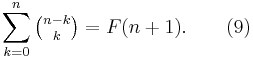

Let F(n) denote the nth Fibonacci number. We obtain a formula about the diagonals of Pascal's triangle

This can be proved by induction using (3) or by Zeckendorf's representation (Just note that the lhs gives the number of subsets of {F(2),...,F(n)} without consecutive members, which also form all the numbers below F(n+1)).

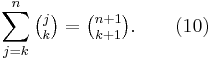

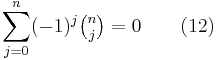

Also using (3) and induction, one can show that

Again by (3) and induction, one can show that for k = 0, ... , n−1

as well as

which is itself a special case of the result from the theory of finite differences that for any polynomial P(x) of degree less than n,

Differentiating (2) k times and setting x = −1 yields this for  , when 0 ≤ k < n, and the general case follows by taking linear combinations of these.

, when 0 ≤ k < n, and the general case follows by taking linear combinations of these.

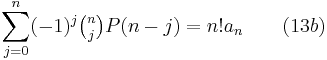

When P(x) is of degree less than or equal to n,

where  is the coefficient of degree n in P(x).

is the coefficient of degree n in P(x).

More generally for 13b,

where m and d are complex numbers. This follows immediately applying (13b) to the polynomial Q(x):=P(m + dx) instead of P(x), and observing that Q(x) has still degree less than or equal to n, and that its coefficient of degree n is dnan.

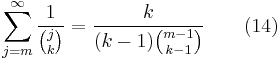

The infinite series

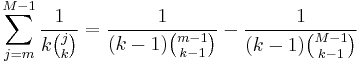

is convergent for k ≥ 2. This formula is used in the analysis of the German tank problem. It is equivalent to the formula for the finite sum

which is proved for M>m by induction on M.

Using (8) one can derive

and

.

.

Identities with combinatorial proofs

Many identities involving binomial coefficients can be proved by combinatorial means. For example, the following identity for nonnegative integers  (which reduces to (6) when

(which reduces to (6) when  ):

):

can be given a double counting proof as follows. The left side counts the number of ways of selecting a subset of ![[n]](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/de504dafb2a07922de5e25813d0aaafd.png) of at least q elements, and marking q elements among those selected. The right side counts the same parameter, because there are

of at least q elements, and marking q elements among those selected. The right side counts the same parameter, because there are  ways of choosing a set of q marks and they occur in all subsets that additionally contain some subset of the remaining elements, of which there are

ways of choosing a set of q marks and they occur in all subsets that additionally contain some subset of the remaining elements, of which there are

The recursion formula

where both sides count the number of k-element subsets of {1, 2, . . . , n} with the right hand side first grouping them into those which contain element n and those which don’t.

The identity (8) also has a combinatorial proof. The identity reads

Suppose you have  empty squares arranged in a row and you want to mark (select) n of them. There are

empty squares arranged in a row and you want to mark (select) n of them. There are  ways to do this. On the other hand, you may select your n squares by selecting k squares from among the first n and

ways to do this. On the other hand, you may select your n squares by selecting k squares from among the first n and  squares from the remaining n squares. This gives

squares from the remaining n squares. This gives

Now apply (4) to get the result.

Continuous identities

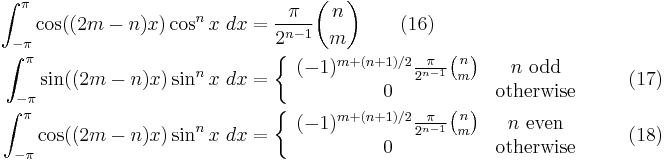

Certain trigonometric integrals have values expressible in terms of binomial coefficients:

For  and

and

These can be proved by using Euler's formula to convert trigonometric functions to complex exponentials, expanding using the binomial theorem, and integrating term by term.

Generating functions

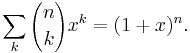

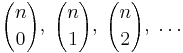

Ordinary generating functions

For a fixed n, the ordinary generating function of the sequence  is:

is:

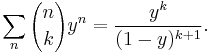

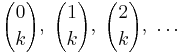

For a fixed k, the ordinary generating function of the sequence  is:

is:

The bivariate generating function of the binomial coefficients is:

Divisibility properties

In 1852, Kummer proved that if m and n are nonnegative integers and p is a prime number, then the largest power of p dividing  equals pc, where c is the number of carries when m and n are added in base p. Equivalently, the exponent of a prime p in

equals pc, where c is the number of carries when m and n are added in base p. Equivalently, the exponent of a prime p in  equals the number of positive integers j such that the fractional part of k/pj is greater than the fractional part of n/pj. It can be deduced from this that

equals the number of positive integers j such that the fractional part of k/pj is greater than the fractional part of n/pj. It can be deduced from this that  is divisible by n/gcd(n,k).

is divisible by n/gcd(n,k).

A somewhat surprising result by David Singmaster (1974) is that any integer divides almost all binomial coefficients. More precisely, fix an integer d and let f(N) denote the number of binomial coefficients  with n < N such that d divides

with n < N such that d divides  . Then

. Then

Since the number of binomial coefficients  with n < N is N(N+1) / 2, this implies that the density of binomial coefficients divisible by d goes to 1.

with n < N is N(N+1) / 2, this implies that the density of binomial coefficients divisible by d goes to 1.

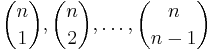

Another fact: An integer n ≥ 2 is prime if and only if all the intermediate binomial coefficients

are divisible by n.

Proof: When p is prime, p divides

for all 0 < k < p

for all 0 < k < p

because it is a natural number and the numerator has a prime factor p but the denominator does not have a prime factor p.

When n is composite, let p be the smallest prime factor of n and let k = n/p. Then 0 < p < n and

otherwise the numerator k(n−1)(n−2)×...×(n−p+1) has to be divisible by n = k×p, this can only be the case when (n−1)(n−2)×...×(n−p+1) is divisible by p. But n is divisible by p, so p does not divide n−1, n−2, ..., n−p+1 and because p is prime, we know that p does not divide (n−1)(n−2)×...×(n−p+1) and so the numerator cannot be divisible by n.

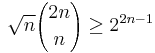

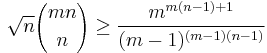

Bounds and asymptotic formulas

The following bounds for  hold:

hold:

Stirling's approximation yields the bounds:

and, in general,

and, in general,  for m ≥ 2 and n ≥ 1,

for m ≥ 2 and n ≥ 1,

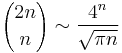

and the approximation

as

as

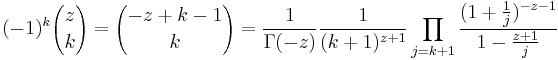

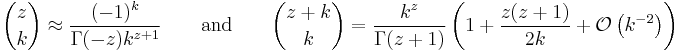

The infinite product formula (cf. Gamma function, alternative definition)

yields the asymptotic formulas

as  .

.

This asymptotic behaviour is contained in the approximation

as well. (Here  is the kth harmonic number and

is the kth harmonic number and  is the Euler–Mascheroni constant).

is the Euler–Mascheroni constant).

The sum of binomial coefficients can be bounded by a term exponential in  and the binary entropy of the largest

and the binary entropy of the largest  that occurs. More precisely, for

that occurs. More precisely, for  and

and  , it holds

, it holds

where  is the binary entropy of

is the binary entropy of  .[3]

.[3]

A simple and rough upper bound for the sum of binomial coefficients is given by the formula below (not difficult to prove)

Generalizations

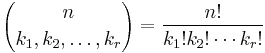

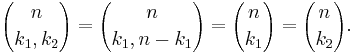

Generalization to multinomials

Binomial coefficients can be generalized to multinomial coefficients. They are defined to be the number:

where

While the binomial coefficients represent the coefficients of (x+y)n, the multinomial coefficients represent the coefficients of the polynomial

See multinomial theorem. The case r = 2 gives binomial coefficients:

The combinatorial interpretation of multinomial coefficients is distribution of n distinguishable elements over r (distinguishable) containers, each containing exactly ki elements, where i is the index of the container.

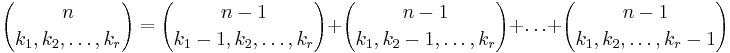

Multinomial coefficients have many properties similar to these of binomial coefficients, for example the recurrence relation:

and symmetry:

where  is a permutation of (1,2,...,r).

is a permutation of (1,2,...,r).

Generalization to negative integers

If  , then

, then  extends to all

extends to all  .

.

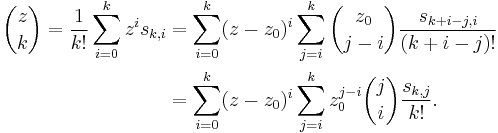

Taylor series

Using Stirling numbers of the first kind the series expansion around any arbitrarily chosen point  is

is

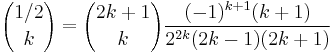

Binomial coefficient with n=1/2

The definition of the binomial coefficients can be extended to the case where  is real and

is real and  is integer.

is integer.

In particular, the following identity holds for any non-negative integer  :

:

This shows up when expanding  into a power series using the Newton binomial series :

into a power series using the Newton binomial series :

Identity for the product of binomial coefficients

One can express the product of binomial coefficients as a linear combination of binomial coefficients:

where the connection coefficients are multinomial coefficients. In terms of labelled combinatorial objects, the connection coefficients represent the number of ways to assign m+n-k labels to a pair of labelled combinatorial objects of weight m and n respectively, that have had their first k labels identified, or glued together, in order to get a new labelled combinatorial object of weight m+n-k. (That is, to separate the labels into 3 portions to be applied to the glued part, the unglued part of the first object, and the unglued part of the second object.) In this regard, binomial coefficients are to exponential generating series what falling factorials are to ordinary generating series.

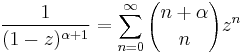

Partial Fraction Decomposition

The partial fraction decomposition of the inverse is given by

and

and

Newton's binomial series

Newton's binomial series, named after Sir Isaac Newton, is one of the simplest Newton series:

The identity can be obtained by showing that both sides satisfy the differential equation (1+z) f'(z) = α f(z).

The radius of convergence of this series is 1. An alternative expression is

where the identity

is applied.

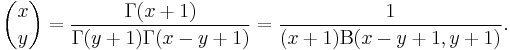

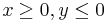

Two real or complex valued arguments

The binomial coefficient is generalized to two real or complex valued arguments using the gamma function or beta function via

This definition inherits these following additional properties from  :

:

moreover,

The resulting function has been little-studied, apparently first being graphed in (Fowler 1996). Notably, many binomial identities fail:  but

but  for n positive (so

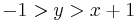

for n positive (so  negative). The behavior is quite complex, and markedly different in various octants (that is, with respect to the x and y axes and the line

negative). The behavior is quite complex, and markedly different in various octants (that is, with respect to the x and y axes and the line  ), with the behavior for negative x having singularities at negative integer values and a checkerboard of positive and negative regions:

), with the behavior for negative x having singularities at negative integer values and a checkerboard of positive and negative regions:

- in the octant

it is a smoothly interpolated form of the usual binomial, with a ridge ("Pascal's ridge").

it is a smoothly interpolated form of the usual binomial, with a ridge ("Pascal's ridge"). - in the octant

and in the quadrant

and in the quadrant  the function is close to zero.

the function is close to zero. - in the quadrant

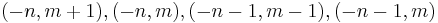

the function is alternatingly very large positive and negative on the parallelograms with vertices

the function is alternatingly very large positive and negative on the parallelograms with vertices

- in the octant

the behavior is again alternatingly very large positive and negative, but on a square grid.

the behavior is again alternatingly very large positive and negative, but on a square grid. - in the octant

it is close to zero, except for near the singularities.

it is close to zero, except for near the singularities.

Generalization to q-series

The binomial coefficient has a q-analog generalization known as the Gaussian binomial coefficient.

Generalization to infinite cardinals

The definition of the binomial coefficient can be generalized to infinite cardinals by defining:

where A is some set with cardinality  . One can show that the generalized binomial coefficient is well-defined, in the sense that no matter what set we choose to represent the cardinal number

. One can show that the generalized binomial coefficient is well-defined, in the sense that no matter what set we choose to represent the cardinal number  ,

,  will remain the same. For finite cardinals, this definition coincides with the standard definition of the binomial coefficient.

will remain the same. For finite cardinals, this definition coincides with the standard definition of the binomial coefficient.

Assuming the Axiom of Choice, one can show that  for any infinite cardinal

for any infinite cardinal  .

.

Binomial coefficient in programming languages

The notation  is convenient in handwriting but inconvenient for typewriters and computer terminals. Many programming languages do not offer a standard subroutine for computing the binomial coefficient, but for example the J programming language uses the exclamation mark: k ! n .

is convenient in handwriting but inconvenient for typewriters and computer terminals. Many programming languages do not offer a standard subroutine for computing the binomial coefficient, but for example the J programming language uses the exclamation mark: k ! n .

Naive implementations of the factorial formula, such as the following snippet in C:

int choose(int n, int k) {

return factorial(n) / (factorial(k) * factorial(n - k));

}

are prone to overflow errors, severely restricting the range of input values. A direct implementation of the multiplicative formula works well:

unsigned long long choose(unsigned n, unsigned k) {

if (k > n)

return 0;

if (k > n/2)

k = n-k; // Take advantage of symmetry

long double accum = 1;

unsigned i;

for (i = 1; i <= k; i++)

accum = accum * (n-k+i) / i;

return accum + 0.5; // avoid rounding error

}

Another way to compute the binomial coefficient when using large numbers is to recognize that

is a special function that is easily computed and is standard in some programming languages such as using log_gamma in Maxima, LogGamma in Mathematica, or gammaln in MATLAB. Roundoff error may cause the returned value not to be an integer.

is a special function that is easily computed and is standard in some programming languages such as using log_gamma in Maxima, LogGamma in Mathematica, or gammaln in MATLAB. Roundoff error may cause the returned value not to be an integer.

See also

- Central binomial coefficient

- Binomial transform

- Star of David theorem

- Table of Newtonian series

- List of factorial and binomial topics

- Multiplicities of entries in Pascal's triangle

- Sun's curious identity

Notes

- ↑ See (Graham, Knuth & Patashnik 1994), which also defines

for

for  . Alternative generalizations, such as to two real or complex valued arguments using the Gamma function assign nonzero values to

. Alternative generalizations, such as to two real or complex valued arguments using the Gamma function assign nonzero values to  for

for  , but this causes most binomial coefficient identities to fail, and thus is not widely used majority of definitions. One such choice of nonzero values leads to the aesthetically pleasing "Pascal windmill" in Hilton, Holton and Pedersen, Mathematical reflections: in a room with many mirrors, Springer, 1997, but causes even Pascal's identity to fail (at the origin).

, but this causes most binomial coefficient identities to fail, and thus is not widely used majority of definitions. One such choice of nonzero values leads to the aesthetically pleasing "Pascal windmill" in Hilton, Holton and Pedersen, Mathematical reflections: in a room with many mirrors, Springer, 1997, but causes even Pascal's identity to fail (at the origin). - ↑ This can be seen as a discrete analog of Taylor's theorem. It is closely related to Newton's polynomial. Alternating sums of this form may be expressed as the Nörlund–Rice integral.

References

- Fowler, David (January 1996). "The Binomial Coefficient Function". The American Mathematical Monthly (Mathematical Association of America) 103 (1): 1–17. doi:10.2307/2975209. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2975209

- Knuth, Donald E. (1997). The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 1: Fundamental Algorithms (Third ed.). Addison-Wesley. pp. 52–74. ISBN 0-201-89683-4.

- Graham, Ronald L.; Knuth, Donald E.; Patashnik, Oren (1994). Concrete Mathematics (Second ed.). Addison-Wesley. pp. 153–256. ISBN 0-201-55802-5.

- Singmaster, David (1974). "Notes on binomial coefficients. III. Any integer divides almost all binomial coefficients". J. London Math. Soc. (2) 8: 555–560. doi:10.1112/jlms/s2-8.3.555.

- Bryant, Victor (1993). Aspects of combinatorics. Cambridge University Press.

- Arthur T. Benjamin; Jennifer Quinn, Proofs that Really Count: The Art of Combinatorial Proof , Mathematical Association of America, 2003.

- Flum, Jörg; Grohe, Martin (2006). Parameterized Complexity Theory. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-29952-3. http://www.springer.com/east/home/generic/search/results?SGWID=5-40109-22-141358322-0.

This article incorporates material from the following PlanetMath articles, which are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License: Binomial Coefficient, Bounds for binomial coefficients, Proof that C(n,k) is an integer, Generalized binomial coefficients.